This is a book summary of Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies by Allen Repko, Rick Szostak, and Michelle Phillips Buchberger (Amazon).

🔒 Premium members get access to the companion synthesis: Interdisciplinary Synthesis: How to be an Interdisciplinarian (+ Infographics)

Quick Housekeeping:

- Pair with: “Interdisciplinary Research” by Repko & Szostak (Book Summary)

- All content in quotation marks is from the authors (content not in quotations is paraphrased).

- All content is organized into my own themes (not necessarily the authors’ chapters).

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Book Summary Contents:

- Comparing Disciplinarities (Multi-, Inter-, Trans-)

- Interdisciplinarity in Detail (+ Infographic)

- Interdisciplinary Cognitive Toolkit

- Interdisciplinary Integration

- Supporting Concepts

Integrating the Disciplines: Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies (Book Summary)

Comparing Disciplinarities (Multi-, Inter-, Trans-)

A discipline is a branch of learning or body of knowledge (such as physics, psychology, or history)—an identifiable but evolving domain of knowledge that its members study using certain tools that serve as a way of knowing that is powerful but constraining.

Disciplinarity:

‘Disciplinarity’ refers to the system of knowledge specialties called disciplines, which is little more than a century old.

- addresses a complex problem by focusing on a problem or the part of a problem that the discipline is interested in.

- can blind us to the broader context (context refers to the circumstances or setting in which the problem, event, statement, or idea exists).

- can produce consequences much like what tunnel vision produces (when it comes to approaching a complex problem, the specialist is able to focus only on the part of the problem that is familiar to the specialist, not on other parts that fall outside the specialist’s area of expertise).

Multidisciplinarity:

Multidisciplinarity is the placing side by side of insights from two or more disciplines without attempting to integrate them (each participating discipline retains its separate identity).

Multidisciplinarity can be compared to a bowl of fruit containing a variety of fruits—each fruit representing a discipline and being in close proximity to the others.

- studies a complex issue, problem, or question from the lenses of two or more disciplines by drawing on their insights but making no attempt to integrate them (how each perspective illumines some aspect of the subject; insights are juxtaposed (i.e., placed side by side) and are added together but not integrated).

- compares perspectives and insights rather than integrating them (and often tacitly prefers one perspective over the others).

- characterized as a juxtapositioning of disciplines (the clearly distinguished and sequential studies simply provide consecutive disciplinary views of the question).

- considers things sequentially (humanities sequentially through literature, then psychology, then biology; but these separate disciplines never intersect upon a well-defined point).

Interdisciplinarity:

Interdisciplinarity subsumes (i.e., includes or absorbs) multidisciplinarity and transcends it (i.e., goes beyond its limits) by means of integration.

Interdisciplinarity is like a smoothie—finely blended so that the distinctive flavor of each fruit is no longer recognizable, yielding instead the delectable experience of the smoothie.

- encompasses any interaction across disciplines.

- studies a complex issue, problem, or question from the perspective of two or more disciplines by drawing on their insights and integrating them (constructs a more comprehensive understanding of the problem).

- addresses a problem comprehensively (the object of inquiry may be an intellectual question or a real-world problem).

Key Point: Disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity are symbiotic (each supports the other)

Most interdisciplinarians do not seek the end of the disciplines; they fully appreciate the invaluable contributions that specialization has made in the production of knowledge. They believe, however, that although the disciplines are useful for producing, organizing, and applying knowledge, a purely specialized approach to learning and knowledge production comes at a very high price: Specialization can blind us to the broader context. Specialization tends to produce tunnel vision. Specialization tends to discount or ignore other perspectives. Specialization can hinder creative breakthroughs. Specialization fails to address complex problems comprehensively. Specialization imposes a past approach on the present. For these reasons, interdisciplinary learning strives to balance disciplinary specialization with interdisciplinary integration.

The underlying premise of interdisciplinary studies is that the disciplines are themselves the necessary precondition for and foundation of the interdisciplinary enterprise. Precondition means prerequisite; it also implies preparation. In other words, developing competence in interdisciplinarity involves understanding the disciplines, their character, and their approach to problem solving. Foundation means the basis on which something stands, like a house standing on a foundation. The disciplines are foundational to interdisciplinary studies because they have produced the perspectives and insights that contribute to our ability as humans to understand our world. Even with the many shortcomings of the disciplines, we need to take them seriously and learn from them as much as we can. In our quest for more comprehensive understandings of, and ultimately solutions to, the many complex problems confronting the worlds of nature and human society, the disciplines are the place where we begin but not where we end.

Transdisciplinarity:

The term ‘transdisciplinarity’ once signaled the pursuit of a unified theory of everything. Today, it often means research that integrates not just across disciplines but across nonacademic sources of insight from stakeholders and practitioners.

- combines interdisciplinarity with a participatory approach (considered to be a type of interdisciplinarity; seeks to use the more comprehensive understanding constructed by interdisciplinary studies to design and implement real-world policy).

- associated with a team approach to research involving academic researchers from different unrelated disciplines as well as nonacademic participants (with an emphasis on case studies).

- seeks to integrate the insights of academics, stakeholders, and nonacademic participants to propose democratic solutions to controversial problems (complex societal or environmental problems of common interest with the goal of resolving them by designing and implementing public policy).

Interdisciplinarity in Detail

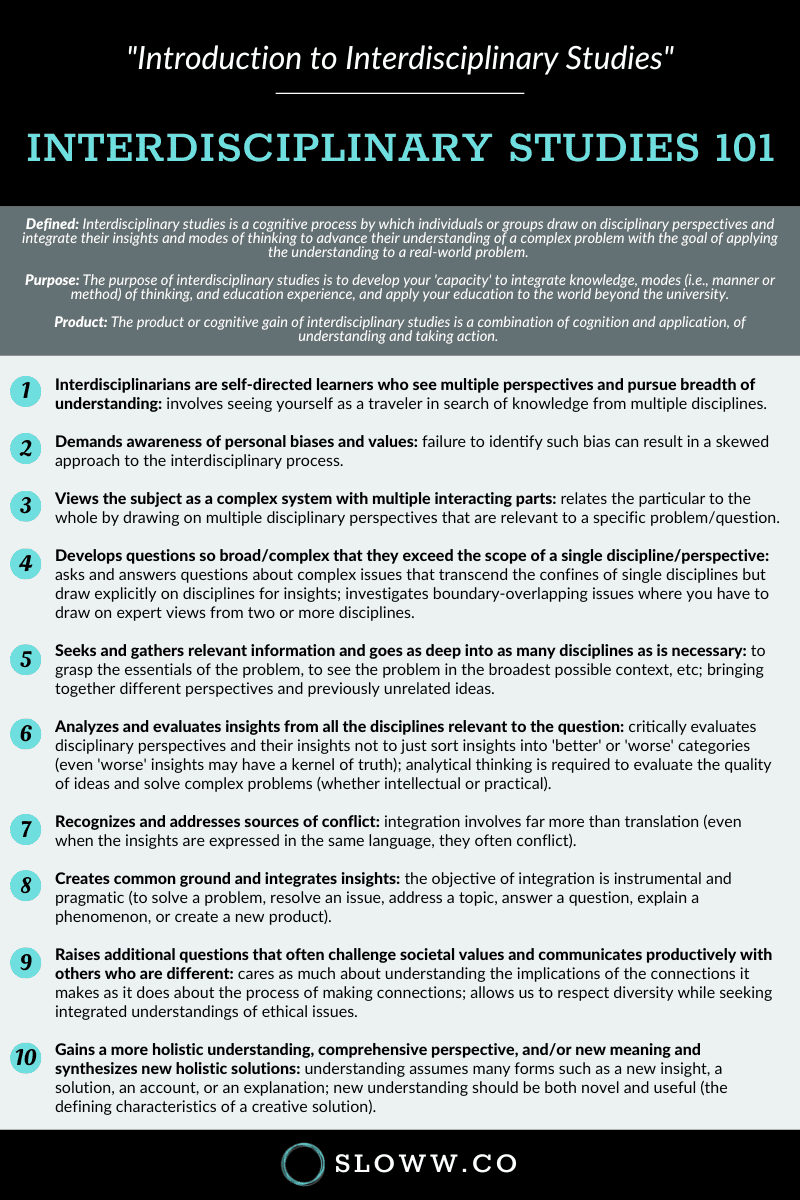

Interdisciplinary studies is a cognitive process by which individuals or groups draw on disciplinary perspectives and integrate their insights and modes of thinking to advance their understanding of a complex problem with the goal of applying the understanding to a real-world problem.

Interdisciplinarity (or interdisciplinarians, interdisciplinary learning/studies, integrative thinking, etc)…

The purpose of interdisciplinary studies is to develop your ‘capacity’ to integrate knowledge, modes (i.e., manner or method) of thinking, and education experience, and apply your education to the world beyond the university (‘capacity’ refers to your cognitive or intellectual ability to think, perceive, analyze, create, and solve problems). Interdisciplinary studies prepares you to engage the real-world complexities.

The product or cognitive gain of interdisciplinary studies is a combination of cognition and application, of understanding and taking action.

- self-directed learners who see multiple perspectives and pursue breadth of understanding (involves seeing yourself as a traveler in search of knowledge from multiple disciplines).

- demands awareness of personal biases and values (failure to identify such bias can result in a skewed approach to the interdisciplinary process).

- views the subject as a complex system with multiple interacting parts (relates the particular to the whole by drawing on multiple disciplinary perspectives that are relevant to a specific problem/question).

- develops questions so broad/complex that they exceed the scope of a single discipline/perspective (asks and answers questions about complex issues that transcend the confines of single disciplines but draw explicitly on disciplines for insights; investigates boundary-overlapping issues where you have to draw on expert views from two or more disciplines).

- seeks and gathers relevant information and goes as deep into as many disciplines as is necessary (to grasp the essentials of the problem, to see the problem in the broadest possible context, etc; bringing together different perspectives and previously unrelated ideas).

- analyzes and evaluates insights from all the disciplines relevant to the question (critically evaluates disciplinary perspectives and their insights not to just sort insights into ‘better’ or ‘worse’ categories (even ‘worse’ insights may have a kernel of truth); analytical thinking is required to evaluate the quality of ideas and solve complex problems whether intellectual or practical).

- recognizes and addresses sources of conflict (integration involves far more than translation—even when the insights are expressed in the same language, they often conflict).

- creates common ground and integrates insights (the objective of integration is instrumental and pragmatic—to solve a problem, resolve an issue, address a topic, answer a question, explain a phenomenon, or create a new product).

- raises additional questions that often challenge societal values and communicates productively with others who are different (cares as much about understanding the implications of the connections it makes as it does about the process of making connections; allows us to respect diversity while seeking integrated understandings of ethical issues).

- gains a more holistic understanding, comprehensive perspective, and/or new meaning and synthesizes new holistic solutions (understanding assumes many forms such as a new insight, a solution, an account, or an explanation; new understanding should be both novel and useful, the defining characteristics of a creative solution).

Instrumental & Critical Interdisciplinarity:

These can be viewed not as mutually exclusive but as occupying opposite ends of a spectrum: At one end is instrumental interdisciplinarity, which sees interdisciplinarity as a way to solve complex practical problems; on the other end is critical interdisciplinarity, which sees interdisciplinarity as a theoretical challenge.

Instrumental interdisciplinarity:

- focuses on research, borrowing from disciplines, and practical problem solving (in response to the demands of society).

- embraces the full diversity of authors and perspectives (rather than rejecting their legitimacy).

- necessitates questioning the disciplines (but does so without being hostile to them; aware that disciplinary understandings are biased but believe that these can be carefully evaluated to reveal less-biased insights that can then be integrated into a more holistic understanding).

- seeks to create commonalities (between conflicting disciplinary insights, integrate these, and construct more comprehensive understandings of complex problems).

Critical interdisciplinarity:

- questions disciplinary assumptions and ideological underpinnings (in some cases, it aims to replace the existing structure of knowledge (i.e., the disciplines) and the system of education based upon it).

- adopts an attitude of suspicion and calls into question not only research data, but also the researcher, the research design, and the interpretation of findings (every part of the research process comes under critical scrutiny for serving elite interests or producing findings that reinforce the status quo).

- rejects the belief that research can be apolitical, objective, and value neutral.

- seek to dismantle boundaries of all kinds and challenge existing power structures (demanding that interdisciplinarity respond to the needs and problems of oppressed and marginalized groups).

- suspicious of holism and integration.

Generalist & Integrationist interdisciplinarians:

No aspect of interdisciplinary studies has generated more controversy among practitioners than that of integration. Interdisciplinarians have been divided into two camps: ‘generalists’ and ‘integrationists.’

Generalist interdisciplinarians:

- reject the notion that integration should be the defining feature (of genuine interdisciplinarity).

- understand interdisciplinarity loosely to mean any form of dialog or interaction between two or more disciplines (while minimizing, obscuring, or rejecting altogether the role of integration).

Integrationist interdisciplinarians:

- regard integration as the key distinguishing characteristic of interdisciplinarity (and the goal of fully interdisciplinary work).

- insist that epistemological and other barriers can be overcome (e.g., conflicting perspectives, insights, and modes of thinking).

Interdisciplinary Cognitive Toolkit

Intellectual capacities, values, traits, skills, and perspective-taking.

Intellectual capacities:

Repeated exposure to interdisciplinary studies fosters the development of certain intellectual capacities, three of which are foundational to interdisciplinarity: perspective taking, critical thinking, and integration.

- Perspective taking: The intellectual capacity to view a problem or subject or artifact from alternative viewpoints, including disciplinary ones, to develop a more comprehensive understanding of it. That is, we come to understand not only how others view something in a particular way, but also why they do so: You cannot really understand how another views things unless you have some idea as to why.

- Critical thinking: The capacity to analyze, critique, and assess. Critical thinking from a detached and comparative viewpoint occurs only in interdisciplinary contexts, where students are challenged to evaluate and integrate the conflicting assumptions and insights of disciplines concerning some complex issue. A second way interdisciplinary studies contributes to the development of critical thinking is to foster ‘intellectual dexterity,’ which is the ability to speak to (if not from) a broad spectrum of knowledge and experience.

- Integration: The heart of the interdisciplinary process. Integration involves critically evaluating disciplinary insights and locating their sources of conflict, creating common ground among them, and constructing a more comprehensive understanding of the problem. The ‘payoff’ of integration is the new understanding.

Values:

Interdisciplinary studies fosters certain values that are guiding principles, mindsets, or attitudes. These become more important when we address issues that deeply concern us. What should become clear as you examine these values is that engaging in interdisciplinary studies may affect the way you think about yourself, your community, your profession, and the world, if you allow it to. These values include empathy, ethical consciousness, humility, appreciation of diversity, tolerance of ambiguity, and civic engagement.

- Empathy: In interdisciplinary work, empathy is limited to understanding the views of others; it does not extend to adopting their views or acting to support them. Otherwise, you engage in the practice common to disciplinary learning: taking sides or adopting a perspective rather than attempting to understand multiple perspectives. To be clear, interdisciplinarians are capable of taking firm positions despite empathy. But interdisciplinarians strive to ground their conclusions in critical thinking rather than perspectival bias.

- Ethical consciousness: Self-knowledge that includes recognition of bias. It means being aware, for example, of the impact of a particular product on the environment and having this awareness affect your decision to purchase or boycott the product. Bias takes two forms here: disciplinary and personal. Disciplinary bias refers to favoring one discipline’s understanding of the problem at the expense of competing understandings of the same problem offered by other disciplines. This is likely to occur simply because you are more familiar with a particular discipline than with others. One useful strategy here is to purposely seek to identify strengths in the insights of disciplines with which you have less familiarity and limitations in the insights of disciplines with which you have the greatest familiarity. Personal bias is often more subtle and refers to allowing your own point of view (e.g., your politics, faith tradition, cultural identity) to influence how you understand or approach the problem. Personal bias manifests itself through selecting materials that agree with your viewpoint, while rejecting those that challenge it or by allowing a particular belief to shape your analysis of the problem. When this happens, the old expression ‘the fix is in’ applies, meaning that the outcome is determined beforehand. Personal bias, no matter how well intentioned, is inconsistent with quality interdisciplinary work.

- Humility: In the context of interdisciplinary studies is a positive attitude of mind that recognizes the limits of one’s training and expertise and seeks to overcome these limits by drawing on expertise from multiple disciplines. It is the awareness that whatever comprehensive understanding you achieve is inevitably incomplete, limited in time and space, and likely to change as knowledge in the disciplines progresses … In short, interdisciplinary humility reflects awareness of both self and reality when confronted by complexity. It is evidenced to the extent that you see the weaknesses of the perspectives closest to your own and the strengths of other perspectives.

- Appreciation of diversity (of ideas and people): Being open to information from any and all relevant sources and having respect for people because of our common humanity. ‘Being open’ does not mean agreeing with or abandoning a critical stance, but being willing, even eager, to learn from different disciplines and other knowledge sources.

- Tolerance of ambiguity: Openness to more than one interpretation, depending on the immediate context.

- Civic engagement: The use of nonpolitical as well as political means to affect the quality of life in a community.

Traits:

Interdisciplinary studies also fosters the development of certain personality traits.

- Entrepreneurship: Involves taking risk to achieve a particular goal. The interdisciplinarian is like an entrepreneur in three ways. Both are eager to venture into a space with which they are unfamiliar. For the entrepreneur, the space is a new market or a new product; for the interdisciplinarian, the space is a new discipline and new insights. Both are able to see possibilities that others do not see. The entrepreneur sees the possibility of meeting an unmet need through the creation of a new process or product; the interdisciplinarian sees the possibility of resolving a problem by creating common ground and integrating insights. And both are able to make connections between different things. The entrepreneur is able to connect, say, two different technologies to create a new product useful for a new purpose; the interdisciplinarian is able to creatively connect two different disciplinary insights in order to produce a more comprehensive understanding of a problem.

- Love of learning: Excitement at the prospect of exploring new ideas, even if these ideas challenge one’s own thinking. Interdisciplinarians are intensely interested in the world and welcome opportunities to view it and its problems from differing perspectives. Finding themselves in new and challenging work situations, they will seek to acquire a working knowledge of relevant terminology and the analytical skills necessary to develop an understanding of a given problem. Interdisciplinarians are not prisoners of bias (either personal or ideological), nor are they impressed by surface explanations of complex problems or simplistic solutions to them. Instead, they are willing to invest the time and intellectual energy to sort through and integrate conflicting viewpoints to achieve an understanding that is more comprehensive.

- Self-reflection: Self-conscious, careful thinking about your behavior and beliefs, why you made certain choices at various points, and how these choices have affected the outcome. Learning, in general, is a process of cognitive and personal transformation that relies heavily on self-reflection, which promotes a stronger self-concept and greater self-knowledge.

- Intellectual courage: It is far easier to ignore the suffering of others than to allow ourselves to feel it. More generally, it is easier to assume that our perspective is right than to recognize why others have different perspectives. And in the act of integrating, we inevitably produce comprehensive insights that are novel: It is generally easier in life to think as others do than to seek to justify novel ideas. Interdisciplinarity requires a capacity, that is, for independence of judgment. We must be willing to experience some discomfort to achieve interdisciplinary understandings. The reward of achieving new understanding will generally far exceed the discomfort experienced along the way.

- Several other traits are implied: It is useful to be patient, as interdisciplinary examination of a question takes time. Interdisciplinary scholars and students need to tolerate ambiguity rather than seek one simple answer to every question. They need to enjoy a challenge and be able to laugh at mistakes they may make along the way. Interdisciplinarians should be open-minded.

Skills:

Interdisciplinary studies fosters the development of important skills, which are competencies in applying knowledge effectively or performing a task creatively. Admittedly, there is some overlap between the intellectual capacities discussed earlier and the skills typically associated with interdisciplinary studies.

- Communicative competence: First, interdisciplinary studies fosters distinctive communicative competency regarding what is being communicated. Persuasive disciplinary communication typically sets out the strengths of one perspective and the limitations of other perspectives; it makes the case that one position is right and others are wrong. Persuasive interdisciplinary communication is concerned with balancing out competing claims, identifying strengths and limitations of every position, and instead of selecting one of the positions, it selects insights from each position to create a new position—one that is responsive to each of the contributing positions but dominated by none of them. As noted above, novel interpretations generally meet resistance, and thus persuasion is of critical importance. Next, interdisciplinary studies fosters distinctive communicative competency regarding the differences between those to whom you are communicating. Here, the focus is on applying the intellectual capacities that we noted earlier: perspective taking, critical thinking, and integration.

- Abstract thinking: Thinking characterized by mental adaptability and flexibility that enable you to use concepts and make generalizations. Abstract thinking is different from concrete thinking, which limits thought to what is right in front of you. The abstract thinker can conceptualize or generalize and understands that a concept may have different meanings in different disciplinary contexts.

- Creative thinking: Thinking that combines previously unrelated ideas or forms a new relationship among ideas. Interdisciplinary studies promotes creative thinking by getting you to look at a problem in new ways, and by challenging you to ask yourself how conflicting insights into the problem might both contain ‘kernels of truth.’ Integrative understandings have to be created: They are necessarily novel combinations of preexisting ideas.

- Metacognition: The awareness of your own learning and thinking processes, often described as ‘thinking about your thinking.’ It involves detaching yourself from your own worldview and attitudes as you think about how you have assembled your own thoughts about things. This is a key skill for interdisciplinarians to develop since interdisciplinary studies is, after all, one large metacognitive process. When you are engaging in interdisciplinary work, you must step back from each discipline that may be relevant to a complex problem and think metacognitively about it—identifying and critically evaluating the way each discipline thinks about the problem. This involves identifying each discipline’s perspective, and in particular, its concepts and theories as well as the assumptions underlying them.

Perspective taking:

Interdisciplinary perspective taking is the intellectual capacity to view a complex problem, phenomenon, or behavior from multiple perspectives, including disciplinary ones, in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of it. Interdisciplinary studies takes on temporarily the perspectives of disciplines but treats them as mere viewpoints. Importantly, taking on other perspectives often involves temporarily setting aside your own beliefs, opinions, and attitudes. Interdisciplinary studies arrives not at a more comprehensive perspective, but at a more comprehensive understanding. The goal is to understand how different insights reflect different perspectives, in order to construct a novel understanding that draws on the best elements of these different insights.

The point of interdisciplinary perspective taking is to gain a more comprehensive perspective on the problem without preferring one perspective over another. Interdisciplinarity moves beyond merely juxtaposing (i.e., laying side by side) different disciplinary perspectives and their insights to integrating these insights to construct a more comprehensive understanding of the problem.

- Viewing yourself: Recognizing the influence of culture, politics, religion, and socioeconomic background on your view of a situation, event, issue, or phenomenon.

- Viewing others: Identifying and examining the perspectives of other people, groups, or organizations, and identifying influences on those perspectives.

- Viewing cultures: Explaining how different access to knowledge, technology, and resources affects cultures.

- Viewing disciplines: Explaining how communities of expertise understand a situation, event, issue, or phenomenon.

Interdisciplinary Integration

Interdisciplinary integration is the cognitive process of critically evaluating disciplinary insights and creating common ground among them to construct a more comprehensive understanding. The new understanding is the product or result of the integrative process.

The idea of interdisciplinary integration finds additional support in the work of linguists George Lakoff and Gilles Fauconnier and cultural anthropologist Mark Turner. Lakoff (1987) introduced the theory of conceptual integration to explain the innate human ability to create new meaning by blending concepts. Fauconnier (1994) deepened our understanding of integration by explaining how our brain takes parts of two separate concepts and integrates them into a third concept that contains some properties (but not all) of both original concepts.

Strategies for integration:

Redefinition, organization, theory extension, and transformation.

- Redefinition: Involves carefully analyzing the way that key concepts are used within different insights. It will often be found that scholars only appear to be disagreeing because they are employing words in different ways.

- Organization: Involves mapping the different arguments made by different authors.

- Theory extension: Involves extending the analysis of one discipline (or an interdisciplinary field) so that it includes insights from other fields. A theory, for example, can be extended to include variables suggested by other disciplines.

- Transformation: Involves placing seeming opposites along a continuum.

Results of integration:

We define ‘more comprehensive understanding’ as a cognitive advancement that results from integrating insights that produces a new whole that would not be possible using single disciplinary means. Authors use a variety of other terms that have similar meanings, such as holistic understanding, interdisciplinary understanding, integrative understanding, and interdisciplinary product; what one calls the understanding that results from integration is a matter of preference.

Unpacking the definition of ‘more comprehensive understanding’ deepens our understanding of it:

- More comprehensive: Means that the interdisciplinary result combines more elements than does any disciplinary understanding or theory.

- Cognitive advancement: Refers to a variety of possible outcomes such as explaining a process, solving a problem, creating a product, or raising a new research question in ways that would have been unlikely through single disciplinary means.

- New: Refers to the improbability of any one discipline or mode of thinking (e.g., Marxism, postmodernism) producing a similar result, and that no one (other than the interdisciplinarian) takes responsibility for studying the complex problem, object, text, or system that falls between the disciplines or that transcends them.

- Whole: Refers to the comprehensiveness of the research result: It cannot be reduced to the disciplinary insights from which it emerged.

Bloom’s taxonomy:

The idea for interdisciplinary integration is grounded in Bloom’s classic taxonomy of levels of intellectual behavior that are involved in learning.

- Drawing on theories of learning and cognitive development, an interdisciplinary team of researchers and educators led by Lorin W. Anderson updated Bloom’s taxonomy in 2001. The team identified six levels within the cognitive domain, with simple recognition or recall of facts at the lowest level through increasingly more complex and abstract mental levels, leading ultimately to the highest order ability, creating.

- The significance of this taxonomy for interdisciplinary studies is that it elevates the cognitive abilities of creating and integrating to the highest level of knowledge. Interdisciplinary creation involves putting elements together—integrating them—to produce something that is new, coherent, and whole. Integration is central to understanding the nature of interdisciplinary studies and is a distinguishing feature of this rapidly growing field. Integration is also at the core of the interdisciplinary process.

Creating common ground:

‘Common ground’ is the knowledge, beliefs, and suppositions that each person must establish with another person in order to interact with that person. That is, certain shared understandings are essential to communication. Common ground is created between conflicting disciplinary insights, assumptions, concepts, or theories and makes integration possible.

- Two people’s common ground is the sum of their mutual, common, or joint knowledge, beliefs, and suppositions.

- Trying to create common ground between two persons from different social, cultural, or political backgrounds is similar to trying to create common ground between conflicting insights from different disciplines. The interdisciplinarian has to create the common assumption, concept, theory, value, or principle that can provide the basis for integration.

- Whether developing a collaborative language for interdisciplinary research teams or integrating conflicting insights, the ‘theory of cognitive interdisciplinarity’ calls for discovering or creating the ‘common ground integrator’ by which conflicting assumptions, theories, concepts, values, or principles can be integrated.

- Common ground involves using various techniques to modify or reinterpret disciplinary elements. Common ground is something that the interdisciplinarian must create. Creating or discovering common ground involves modifying or reinterpreting disciplinary elements (i.e., assumptions, concepts, or theories) that conflict. Modifying these elements to reduce the conflict between them involves using various techniques.

- Common ground is that which is created between conflicting disciplinary insights, assumptions, concepts, or theories and makes integration possible.

Broad Model:

The ‘Broad Model’ reflects the instrumentalist focus on problem solving and subsumes the approaches of contextualization, conceptualization, and problem centering.

The Broad Model…

- draws on all disciplines for insights (whether they are epistemologically distant or close).

- uses all disciplinary tools (including assumptions, concepts, theories, and methods to study a problem).

- maps complex problems (to reveal their complexity and causal links).

- critically evaluates disciplinary insights as well as stakeholder views (recall that we can use similar techniques for integrating beyond the academy as within the academy).

- makes the process of integration explicit and transparent (by breaking it down into discrete STEPS (that require reflecting on earlier STEPS).

- creates common ground among disciplinary insights on the basis of one or more key assumptions, concepts, or theoretical explanations (thereby melding conflicting insights until the contribution of each becomes inseparable).

Broad Model integrative approaches:

- Integrative Approach 1: Contextualization is an approach used by humanists and those in the fine and performing arts to embed the object of study in the fabric of time, culture, and personal experience. Under this approach, the process of integration is not standardized, and it varies from context to context. Contextualization is the practice of placing a text, or author, or work of art into context, to understand it in part through an examination of its historical, geographical, intellectual, or artistic location.

- Integrative Approach 2: Conceptualization seeks to make meaning from different concepts that, on the surface, have no apparent connection or commonality. The approach is based on a general theory of cognition that describes how elements from different contexts are ‘blended’ in a subconscious process known as ‘conceptual blending’ thought to be common in everyday thought and language.

- Integrative Approach 3: Problem-centering approach uses issues of public debate, product development, or policy intervention as focal points for making connections between disciplines and integrating their insights … The epistemological goal of this model is not so much to make knowledge personally meaningful (as in contextualization), or to advance fundamental knowledge (as in conceptualization), but to attack a pressing problem by drawing on all available disciplinary tools in order to resolve it.

Supporting Concepts

This is a list of related concepts worth knowing.

Analytical & Creative Intelligence:

- Analytical intelligence: The ability to break a problem down into its component parts, solve problems, and evaluate the quality of ideas.

- Creative intelligence: The ability to formulate ideas and make connections.

Contextual & Systems Thinking:

- Contextual thinking: The ability to view a subject from a broad perspective by placing it in the fabric of time, culture, or personal experience (characterized by wholeness, by the relationship between parts, and by the assumption that knowledge changes).

- Systems thinking: The ability to break a problem down into its constituent parts to reveal internal and external influences, figure out how each of these parts relates to the others and to the problem as a whole, and identify which parts different disciplines address.

Close Reading & Critical Reflection:

- Close reading: Calls for careful analysis of a text that begins with attending to individual words, sentence structure, and the order in which sentences and ideas unfold.

- Critical reflection: The process of analyzing, questioning, and reconsidering the activity (cognitive or physical) that you are engaged in.

Deductive & Inductive Approaches:

- Deductive approach: Calls for the researcher to develop a logical explanation or theory about a phenomenon, formulate a hypothesis that is testable, and then make observations and compile evidence to confirm or deny the hypothesis.

- Inductive approach: Begins with making systematic observations, detecting patterns, formulating tentative hypotheses about these patterns, and then formulating a theory that explains the phenomenon in question.

Critical Pluralism & Multiplicity:

- Critical pluralism: Students who are critical pluralist thinkers believe that knowledge can be objective but not certain and absolute as dualists assume. Critical pluralists accept the pluralism of relativism without drawing the relativist conclusion that ‘anything goes.’ Critical pluralists view multiple and conflicting disciplinary perspectives on a subject as more or less well-reasoned judgments. So, when presented with a range of disciplinary perspectives on a subject, critical pluralists view each as partial and none as complete.

- Multiplicity: When you experience several plausible yet contradictory explanations of the same phenomenon as opposed to one simple, clear-cut, unambiguous explanation. Such multiplicity is a key feature of interdisciplinary studies when working with conflicting insights coming out of different disciplinary perspectives. The reward for grappling with multiplicity is the ability to integrate across differing insights to achieve a more comprehensive understanding. Though you should be willing to move away from clinging stubbornly to one ‘right’ answer, you need not and should not abandon the hope that we can achieve ‘better’ answers by evaluating and integrating multiple insights.

You May Also Enjoy:

- See all book summaries and book recommendations/reading list

- Make It Stick by Peter Brown, Henry Roediger III, and Mark McDaniel | Book Summary | 🔒 How to Apply It

- Range by David Epstein | Book Summary

- Ultralearning by Scott Young | Book Summary

- A Synthesizing Mind by Howard Gardner | Book Summary

- Metathinking by Nick Shannon and Bruno Frischherz | Book Summary

- How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler | Book Summary | 🔒 How to Apply It

- How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens | Book Summary 1, 2 | 🔒 How to Apply It

Leave a Reply