After wrapping up Meditations by Marcus Aurelius (book summary and top quotes), I decided to stay on the theme of philosophy and Stoicism by reading Enchiridion by Epictetus.

The first thing you’ll need to do when you want to read any ancient book is pick a translation. After some quick research on Enchiridion, it sounds like a favorite paid translation is Robin Hard (Amazon) and go-to free translations are George Long and Elizabeth Carter (free online). George Long also has a popular free translation of Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. So, you could have some consistency by reading the same translator for Enchiridion by Epictetus.

Since I opted for a modern translation of Meditations, I decided to do the same for Enchiridion and went with Discourses, Fragments, Handbook (Oxford World’s Classics) by Robin Hard (Amazon).

If you’re interested in a short video summary of Enchiridion, this is the best one I found:

Quick Housekeeping:

- All quotes are from Epictetus translated by Robin Hard unless otherwise stated.

- I’ve added emphasis (in bold) to quotes throughout this post.

- For quick access if you buy the book (or want to cross-reference various translations), I’ve shown the passage/chapter number at the end of each quote.

Post Contents: Click a link here to jump to a section below

Intro to Epictetus & Enchiridion (by Robin Hard):

15 Top Themes from Enchiridion by Epictetus:

- Fate

- Nature & God(s)

- Character

- Power & Control

- Desire & Aversion

- Judgement

- Training Your Mind

- Choice

- Progress

- Purpose

- Speech

- Action

- Tradeoffs

- Simplicity

- Death

Intro to Epictetus & Enchiridion (by Robin Hard)

About Epictetus (by Robin Hard)

“A recurrent theme of Epictetus’ teachings is that studying philosophy is not just a matter of interpreting texts or developing facility in intellectual activities, notably logical reasoning. It is a matter of learning to give an overall shape and purpose to your life and of using your understanding to inform all aspects of your actions, attitudes, and relationships.”

- “Epictetus ( c .50– c .135) was an influential teacher of Stoic ethical philosophy.”

- “He (Epictetus) aims to show that Stoic ethics can have a transforming influence on the way you live and offers a powerful pathway to human happiness.“

- “They have attracted the interest of many readers and thinkers in later antiquity and from the sixteenth century to the present. In the modern world, Epictetus helped to shape the development of cognitive psychotherapy and is becoming more widely used in ‘guide-to-life’ writings.”

About Enchiridion, the Handbook or Manual (by Robin Hard)

“The Discourses and Handbook are forceful, direct, and challenging, and are expressed in a way that is accessible to a very wide range of people. They set out the core ethical principles of Stoicism in a form designed to help people put them into practice and to use them as a basis for leading a good human life.”

- “Arrian ( c .86–160), later an important historian, studied with Epictetus in his youth, perhaps in 107–9. Arrian recorded and published Epictetus’ informal lectures and conversations on ethics, in eight books, of which four books and some fragments survive. These are the Discourses; Arrian also wrote a summary of main themes, the Handbook or Manual (Enchiridion).”

- “The Handbook (Greek, Encheiridion) is a selection by Arrian of themes taken from the Discourses, of which there were originally eight books. The passages (or ‘chapters’) are of different types. Some (e.g. 1, 2, 5, 30–1) seem to be designed to provide concise and striking formulations of ideas that recur throughout the Discourses (presumably, including those we have lost). Many passages offer specific advice about what practices to adopt in order to set about living the kind of philosophical life recommended by Epictetus (e.g. 3, 4, 6, 10, 11, 12). One passage (33) exceptionally consists of a series of short pieces of moral advice that are not obviously related to Epictetus’ normal Stoic framework.”

- “The Handbook has been much used, from Marcus Aurelius onwards, as a source of Stoic ethical advice for ‘self-help’ or ‘guide to life purposes’”.

- “The Handbook and Discourses of Epictetus have been probably the most widely read and influential of all Stoic texts from their first appearance until now.”

A Handbook for Living: 15 Top Themes from Enchiridion by Epictetus (Book Summary)

1. Fate

“Remember that you’re an actor in a play, which will be as the author chooses, short if he wants it to be short, and long if he wants it to be long. If he wants you to play the part of a beggar, act even that part with all your skill; and likewise if you’re playing a cripple, an official, or a private citizen. For that is your business, to act the role that is assigned to you as well as you can; but it is another’s part to select that role.” (17) (Author’s Note: “Another” refers to “God, conceived as source of providential fate”)

- “Don’t seek that all that comes about should come about as you wish, but wish that everything that comes about should come about just as it does, and then you’ll have a calm and happy life.” (8)

2. Nature & God(s)

“Just as a target isn’t set up to be missed, so nothing that is bad by nature comes into being in the universe.” (27)

- “The will of nature may be learned from those events in life in which we don’t differ from one another.” (26)

- “…don’t look to what he is doing, but to what you must do if you are to keep your choice in harmony with nature. For no one will cause you harm if you don’t wish it; you’ll have been harmed only when you suppose that you’ve been harmed.” (30)

- “As regards piety towards the gods, you should know that the most important point is to hold correct opinions about them, regarding them as beings who exist and govern the universe well and justly, and to have made up your mind to obey them and submit to everything that comes about, and to fall in with it of your own free will, as something that has been brought to pass by the highest intelligence. For if you follow that course, you’ll never find fault with the gods or accuse them of having neglected you.” (31.1)

3. Character

“The condition and character of a layman is this: that he never expects that benefit or harm will come to him from himself, but only from externals. The condition and character of a philosopher is this: that he expects all benefit and harm to come to him from himself.” (48.1)

- “Lay down from this moment a certain character and pattern of behaviour for yourself, which you are to preserve both when you’re alone and when you’re with others.” (33.1)

- “Whatever rules of conduct are set for you, hold to them as if they were laws, as if it would be an act of impiety for you to transgress them; as to what anyone says about you, pay no heed to it, since in the end that is not your concern.” (50)

4. Power & Control

“Some things are within our power, while others are not. Within our power are opinion, motivation, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever is of our own doing; not within our power are our body, our property, reputation, office, and, in a word, whatever is not of our own doing.” (1.1)

- “…if you regard only that which is your own as being your own, and that which isn’t your own as not being your own (as is indeed the case), no one will ever be able to coerce you, no one will hinder you, you’ll find fault with no one, you’ll accuse no one, you’ll do nothing whatever against your will, you’ll have no enemy, and no one will ever harm you because no harm can affect you.” (1.3)

- “Everyone is subject to anyone who has power over what he wants or doesn’t want, as one who is in a position to confer it or take it away. If anyone wants to be free, then, let him neither want anything nor seek to avoid anything that is under the control of others; or else he is bound to be a slave.” (14.2)

- “But for me every omen is favourable for I want it to be so; for whatever may come about, it is within my power to derive benefit from it.” (18)

5. Desire & Aversion

“Remember that desire promises the attaining of what you desire, and aversion the avoiding of what you want to avoid, and that he who falls into desire is unfortunate, while he who falls into what he wants to avoid suffers misfortune.” (2.1)

- “For the present, however, suppress your desires entirely; for if you desire any of the things that are not within our power, you’re bound to be unfortunate, while those that are within our power, which it would be right for you to desire, aren’t yet within your reach.” (2.2)

- “For where a person’s interest lies, there too lies his piety. It follows that whoever takes care to exercise his desires and aversions as he ought is taking care at the same time that he’ll act with piety.” (31.4)

6. Judgement

“It isn’t the things themselves that disturb people, but the judgements that they form about them.” (5)

- “Practise, then, from the very beginning to say to every disagreeable impression, ‘You’re an impression and not at all what you appear to be.‘” (1.5)

- “So accordingly, whenever we’re impeded, disturbed, or distressed, we should never blame anyone else, but only ourselves, that is to say, our judgements.” (5)

- “It is the act of an ill-educated person to cast blame on others when things are going badly for him; one who has taken the first step towards becoming properly educated casts blame on himself; while one who is fully educated casts blame neither on another nor on himself.” (5)

- “So whenever anyone irritates you, recognize that it is your opinion that has irritated you. Try above all, then, not to allow yourself to be carried away by the impression; for if you delay things and gain time to think, you’ll find it easier to gain control of yourself.” (20)

7. Training Your Mind

“For it is better to die of hunger, but free from distress and fear, than to live in plenty with a troubled mind.” (12.1)

- “If someone handed over your body to somebody whom you encountered, you’d be furious; but that you hand over your mind to anyone who comes along, so that, if he abuses you, it becomes disturbed and confused, do you feel no shame at that?” (28)

- “It is a sign of a lack of natural aptitude to spend much time on things relating to the body, by taking a large amount of exercise, for instance, and eating too much, drinking too much, and spending too much time emptying one’s bowels and copulating. No, these things should be done in passing, and you should devote undivided attention to your mind.” (41)

8. Choice

“Disease is an impediment to the body, but not to choice, unless choice wills it to be so. Lameness is an impediment to the leg, but not to choice. And tell yourself the same with regard to everything that happens to you; for you’ll find that it acts as an impediment to something else, but not to yourself.” (9)

- “With regard to everything that happens to you, remember to look inside yourself and see what capacity you have to enable you to deal with it.” (10)

- “…every outcome is indifferent and of no concern to you, and that whatever it may be, it will be possible for you to make good use of it, and that no one can prevent you from doing so.” (32.2)

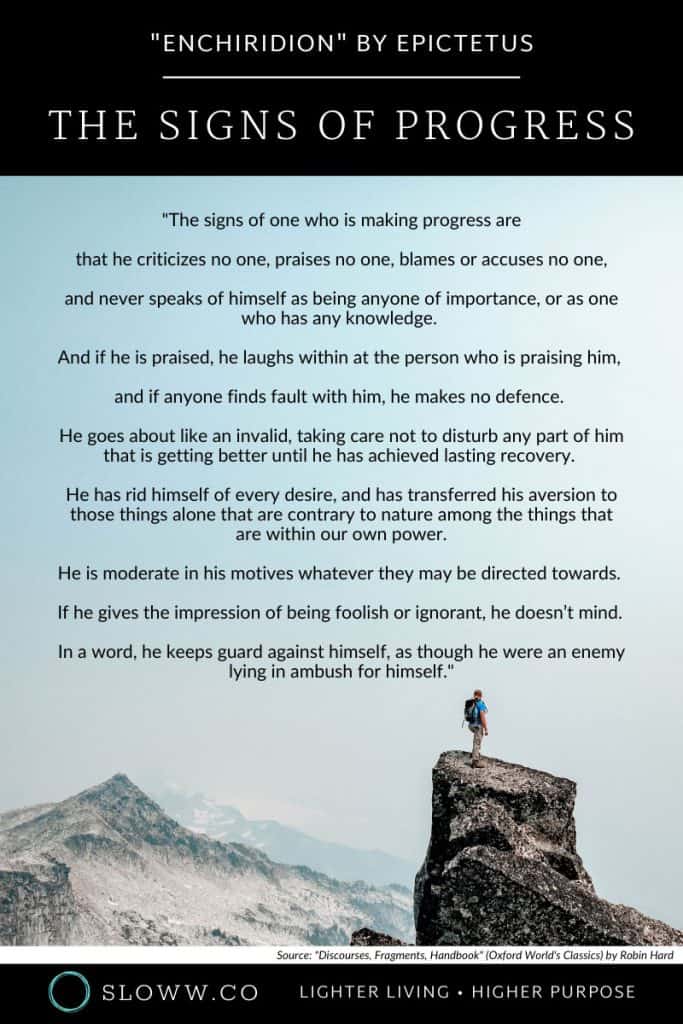

9. Progress

“If you want to make progress, put up with being thought foolish and silly with regard to external things, and don’t even wish to give the impression of knowing anything about them.” (13)

- “The signs of one who is making progress are that he criticizes no one, praises no one, blames or accuses no one, and never speaks of himself as being anyone of importance, or as one who has any knowledge. And if he is praised, he laughs within at the person who is praising him, and if anyone finds fault with him, he makes no defence. He goes about like an invalid, taking care not to disturb any part of him that is getting better until he has achieved lasting recovery. He has rid himself of every desire, and has transferred his aversion to those things alone that are contrary to nature among the things that are within our own power. He is moderate in his motives whatever they may be directed towards. If he gives the impression of being foolish or ignorant, he doesn’t mind. In a word, he keeps guard against himself, as though he were an enemy lying in ambush for himself.” (48.2-3)

- “So you should think fit from this moment to live as an adult and as one who is making progress; and let everything that seems best to you be an inviolable law for you. And if you come up against anything that requires an effort, or is pleasant, or is glorious or inglorious, remember that this is the time of the contest, that the Olympic Games have now arrived, and that there is no possibility of further delay, and that it depends on a single day and single action whether progress is to be lost or secured.” (51.2)

- “And even if you’re not yet a Socrates, you ought to live like someone who does in fact wish to be a Socrates.” (51.3)

10. Purpose

“And how will you be ‘nobody anywhere’ if you only need to be somebody in those things that are within your own power, and in which it is possible for you to be a man of the highest worth?” (24.1)

- “If you set your desire on pursuing philosophy, prepare from that moment to be subject to ridicule, and to have many people mocking you…You shouldn’t assume an air of self-importance, but should hold fast to the things that seem best to you, as one who has been appointed by God to this post; and remember that if you hold true to the same principles, those who laughed at you will later come to admire you…” (22)

- “…it is enough that each person fulfils his own function.” (24.4)

11. Speech

“Remain silent for the most part, or say only what is essential, and in few words.” (33.2)

- “Never call yourself a philosopher, and don’t talk among laymen for the most part about philosophical principles, but act in accordance with those principles…And accordingly, if any talk should arise among laymen about some philosophical principle, keep silent for the most part, for there is a great danger that you’ll simply vomit up what you haven’t properly digested.” (46.1-2)

- “The following assertions don’t form a coherent argument: ‘I’m richer than you, therefore I’m better than you’ or ‘I’m more eloquent than you, therefore I’m better than you’; no, it is these that do: ‘I’m richer than you, therefore my possessions are superior to yours’ or ‘I’m more eloquent than you, therefore my way of speaking is superior to yours.’ But you yourself are neither your possessions nor your way of speaking.” (44)

12. Action

“In each action that you undertake, consider what comes before and what follows after, and only then proceed to the action itself.” (29)

- “But use only your motives to act or not to act, and even those lightly, with reservations and without straining.” (2.2)

- “Make a start, then, with small things.” (12.1)

- “Just as, when walking around, you take care not to tread on a nail or sprain your ankle, so take care likewise to avoid harming your ruling centre; and if we observe this rule in every action, we’ll undertake the task in a more secure fashion.” (38)

13. Tradeoffs

“For you should recognize that it isn’t easy to keep your choice in accord with nature and, at the same time, hold onto externals, but if you apply your attention to one of those things, you’re bound to neglect the other.” (13)

- “For nothing can be acquired at no cost at all.” (12.2)

- “When you receive an impression of some pleasure, take care not to get carried away by it, as with impressions in general; but rather, make it wait for you, and allow yourself some slight delay. And next, think about these two moments in time, that in which you’ll enjoy the pleasure, and that in which you’ll come to repent after having enjoyed it and will reproach yourself; and set against all of that how you’ll rejoice if you’ve abstained from the pleasure, and will congratulate yourself for having done so. If you think, however, that a suitable occasion has come for you to engage in this task, take care that you’re not overcome by its allure, and by the pleasantness and attraction of it; but set against this the thought of how much better it is to be conscious of having gained a victory over it.” (34)

14. Simplicity

“In things relating to the body, take only as much as your bare need requires, with regard to food, for instance, or drink, clothes, housing, or household slaves; but exclude everything that is for show or luxury.” (33.7)

- “When you’ve become adapted to a simple way of life in bodily matters, don’t pride yourself on that, and likewise, if you drink nothing but water, don’t proclaim at every opportunity that you drink nothing but water.” (47)

15. Death

“Day by day you must keep before your eyes death and exile and everything else that seems frightening, but most especially death; and then you’ll never harbour any mean thought, nor will you desire anything beyond due measure.” (21)

You May Also Like:

- See all book summaries